In early February 2024, news broke of a proposed class action lawsuit against Johnson and Johnson for breach of their fiduciary duty under ERISA, also known as the Employee Retirement Income and Security Act. The plaintiff is suing J&J and their health plan fiduciaries for “failing to negotiate lower prices for prescription drugs, which cost workers millions of dollars in overpayments for generic drugs”.

One major complaint in the lawsuit is that Johnson and Johnson’s pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) was allowed to define generic specialty drugs however they saw fit and required any prescriptions for generic specialty drugs be filled by their own specialty pharmacy. This allowed the fiduciaries to control both what was paid and what was charged for those particular drugs – many times the costs for these drugs were thousands of percent higher than the cost would have been at local pharmacies.

As with all contracts, the devil is in the details. While varying definitions of plan terminology may not seem to be a big deal at first, slight differences in the verbiage can have major, even detrimental, impacts to plan costs. In light of this notable case, we’ve compiled several examples of how the same terms can be defined very differently across different PBM contracts.

Average Wholesale Price (AWP)

This term is is the basis for pricing brand name drugs in most PBM contracts, where the contract stipulates some discount off of AWP, illustrated as AWP – X%. For the discount to be meaningful, there needs to be consensus on the definition of AWP and its source. In the first example below, you will note that the PBM/Plan Administrator has the ability to pick and choose the “pricing source” i.e. source of AWP, as they see fit. This allows far too much leeway for the PBM, where the second example of AWP explicitly states the source.

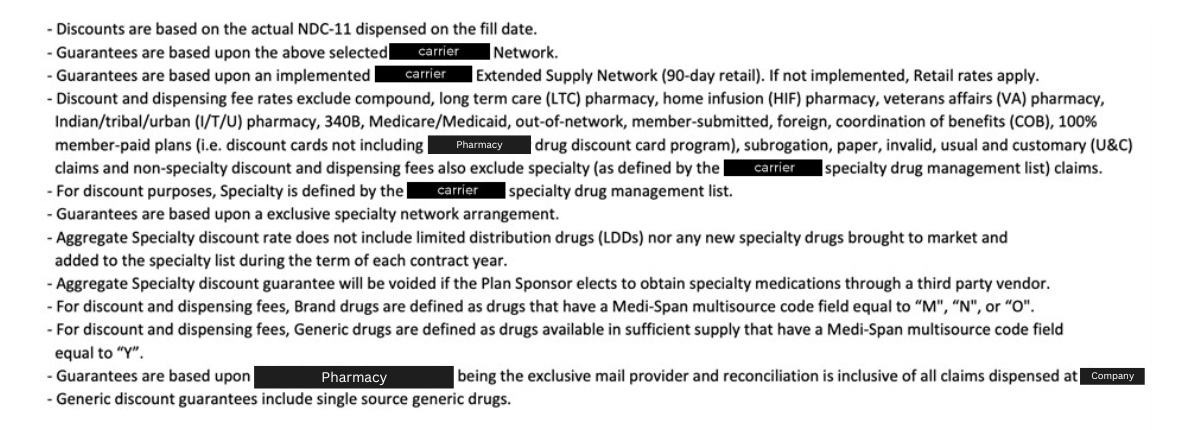

Generic Drugs

One would think that coming to terms with the definition of a generic drug should be a simple thing, but as the following examples illustrate, it is anything but simple. PBM’s will often include “guarantees” in their contracts surrounding their performance in delivering the promised discounts, which are commonly broken down by drug class (i.e. Brand, Generic, Specialty). By leveraging a nebulus definition of generic and/or brand name drugs, the PBM can manipulate where a drug falls to their benefit. The more explicit the definition of each class, the better.

Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC)

MAC is similar to AWP for brand name drugs, but it is the basis for establishing what a plan will pay for generic drugs. If a PBM is allowed to maintain multiple MAC lists, it allows them to charge the plan one price while paying a pharmacy a different price. This is called “spread pricing” and is highlighted to quite a degree in the Johnson and Johnson lawsuit. You will note in one of the examples below that the PBM clearly calls out the existence of “list(s)”. They also reference the proprietary nature of the “list(s)” and therefore the inability of the plan sponsor to verify what actually is occurring.

Specialty Drugs/Pharmacies

The variability of the definition of “Specialty Drugs” or “Specialty Pharmacy” allows a PBM to play similar games as they do between brand and generic drugs. In addition, as highlighted in the Johnson and Johnson suit, defining a product as “specialty” allows many PBM’s to redirect the sourcing of the medication to their own specialty pharmacy, which allows them to fully control the price to their benefit. The examples below illustrate just how variable the definition can be.

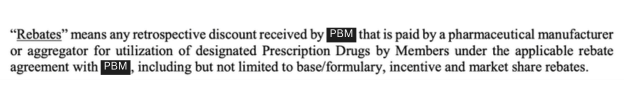

Rebates

Most plan sponsors are aware of the fact that brand name prescription drugs include rebates which are incentives from the drug manufacturer to place their drug in a favorable position on a drug formulary. Rebates are the return of money that the plan sponsor and/or plan participant already paid, and therefore should be returned fully to the plan. PBM’s and commercial insurance carriers, however, have found rebates to be a very lucrative source of income and therefore they do all they can to retain as much of them as possible. One way they do so is by simply renaming the rebate something else. If they promise to return the “rebates” to the plan sponsor, but it isn’t called a “rebate” then they can just keep the money. Take a look at the examples from different PBM contracts below and tell us which example is better for the plan sponsor.

While we have no immediate concerns that other particular employers would be hit with a similar lawsuit, we want to emphasize the importance of understanding the provisions of the PBM contract you have, paying attention to definitions like the ones we’ve outlined above.

We would be happy to sit down with you to review your contract and point out areas for improvement. Contact the Total Control Health Plans team today to connect with a member of our team.